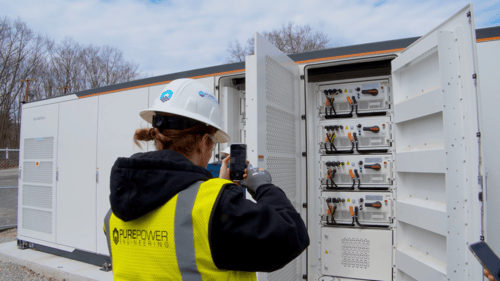

Driven by grid stability & reliability needs and by the integration of renewables, Standalone BESS (battery energy storage systems) are moving from pilot to mainstream. But anyone who has tried to develop or engineer one, especially in dense, highly regulated environments, knows these are not “just like any other project.” As one engineer in our discussion put it, a standalone BESS “comes with a package of auxiliary equipment" and "two-way power flow and protection requirements that make them fundamentally more complex."

Drawing on recent projects, this article distills the key design considerations for Standalone BESS: augmentation, reactive power and load flow, interconnection strategy, auxiliary systems and space planning, and safety/grounding. Wherever possible, we’ve included direct insights from our team’s round table to keep it practical and specific.

.png?width=464&height=261&name=BESS%20Article%20Thumbnail%20Template%20(2026).png)

1. Augmentation - Planning for Tomorrow’s Capacity

Augmentation is a core Standalone BESS design decision. As Matt Donovan, Director of Engineering Standards, noted, “augmentation basically means planning for future capacity.” In theory, you set aside space and electrical capacity to add cabinets or containers years down the road as batteries degrade or economics evolve. In practice, it’s complicated:

Technology is evolving fast. “This may be an ongoing discussion as people discover more and more about overbuild strategies,” Assistant Project Manager, Lakhan Wadhwa, PE, said. Battery lifetimes, once modeled conservatively, are now stretching “up to 20 years of lifespan on some of these batteries”, which changes augmentation timing and economics.

Takeaway: Treat augmentation as a sitewide program, not a single line item. Reserve physical space (access paths), and future electrical capacity, but validate against the utility’s interconnection and operational constraints so the “future you” can actually plug in more BESS without rebuilding the site.

2. Reactive Power - VARs Can Shrink Revenue

Reactive power requirements are showing up on every Standalone BESS project our team is seeing, especially in front-of-the-meter applications. And they materially affect revenue.

Mudit Bareja, PE, Project Manager, shared an example: on a 5 MVA system, the utility required up to 44% of the capacity for reactive power (VAR). That meant the system could only deliver about 4.4–4.5 MW of real power instead of the expected 4.9 MW—a loss of roughly half a megawatt. For developers, that shortfall can turn a profitable project into a marginal one.

For smaller projects, you might estimate with the power triangle (S² = P² + Q²). But, as Matt cautioned, “when you get into bigger systems, impedance in the cables and transformers becomes significant, and the simple math starts to break down.” That’s when you need a load flow study: “verify that your system can meet utility requirements at the point of interconnection with a load flow study.”

Design moves that help:

• Overbuild KVA so your inverters and transformers can provide required VARs without starving real power.

• Model early, model often. Incorporate detailed load flow into development engineering so finance teams don’t build a profit & loss around 1.0 MW of export when VARs will cap you at 0.85–0.95 MW.

• Differentiate by project size. Quick math might work for small DG; larger sites need full steady state and dynamic studies.

Quick Primer: What Are VAR and kVA?

kW (kilowatts) - measures real power, aka the portion of electricity that can do actual work. This is the primary source of revenue.

kVAR (kilovolt-ampere reactive) - measures reactive power, aka the portion of electricity that sustains magnetic and electric fields in AC systems but doesn’t perform useful work. It’s essential for voltage stability.

kVA (kilovolt-amperes) - measures apparent power, which combines real power (kW) and reactive power (kVAR). It represents the total power flowing in the circuit.

The relationship between them is expressed by the power triangle: S2=P2+Q2

Where:

• S = Apparent Power (kVA)

• P = Real Power (kW)

• Q = Reactive Power (kVAR)

3. Interconnection Strategy - The Make-or-Break Item

BESS Interconnection varies dramatically by utility and location. In New York City, it’s complex and costly: “even though people have Megapacks sitting, they may be deterred just by seeing the interconnection costs.” What started as “simple” utility approach has evolved into redundant, more sophisticated schemes that can add millions in scope.

Outside NYC, you may find smoother pathways. Lakhan pointed to Massachusetts as a place where interconnection can be more straightforward for BESS, but local codes might still drive significant life safety scope: fire engineering, CMU/blast walls, tightly controlled expensive grounding systems, detection/suppression systems, and strict access and spacing rules. The net effect is the same: interconnection strategy belongs at the very front of siting and layout, not at the end.

Checklist to de-risk interconnection:

• Start with the utility. Clarify VAR obligations, ramp rates, charge/discharge windows, SCADA, and remote control expectations up front.

• Budget a range for grid upgrades. In constrained grids, set realistic contingencies to avoid late-stage sticker shock.

• Coordinate with the AHJ early. “There is more educating of AHJs than the utility,” Mudit noted. Early alignment pays back in fewer redesigns and shorter review cycles.

4. Auxiliary Systems & Space Planning - The Hidden Half of Standalone BESS

Unlike PV, a Standalone BESS is bidirectional. That means more controls, more protection, and more auxiliary power to keep it all online:

• Protection & controls: Expect directional power elements, SCADA, a site controller, and a Battery/Energy Management System orchestrating charge/discharge to meet utility export/import limits & ramp-rates. “We don’t want the relay to trigger and disconnect the whole system,” Mudit said—that’s why the BMS/EMS should handle modulation, with protection as the backstop.

• Access and constructability: Manufacturers impose real, physical constraints. For example, Tesla Megapack pads are specified with a slight tilt (≈2°) and require forklift access and turnaround radius. In tight urban sites, our team optimized layouts with multiple access points instead of one, to satisfy handling requirements without 15 ft turnaround bubbles.

Bottom line: Lay out your Standalone BESS yard as a working industrial site, not just a container garden; crane paths, forklift lanes, door swing, O&M removal paths, equipment working clearances, and safe keepout zones all matter.

5. BESS Safety & Grounding - Design for People, Not Just Equipment

In urban settings, step and touch potential is a top tier risk because the public may be within feet of medium voltage equipment (15–33 kV). Grounding studies on recent projects revealed touch potentials “a lot higher than it’s supposed to be,” requiring remedies.

What’s Working:

• Engineered grounding (rings, meshes, rods) tailored to the site. In NYC, where “we’re edge to edge,” we couldn’t place an exterior ground ring offset from the fence, so we combined CMU walls (which we also needed for two hour fire/blast rating) with refined internal grounding to keep touch voltages in limits.

• Fire mitigation that fits the chemistry and AHJ. There’s an active debate on water vs. alternative agents for lithium-ion incidents. Some sites are tied to hydrants; others use specialized suppression. What’s non-negotiable is detection, compartmentalization, and containment, hence the prevalence of concrete barriers/blast walls to prevent propagation.

6. Language Matters: BESS vs. ESS

The industry still uses BESS casually, but many codes and standards say ESS (Energy Storage Systems) because storage can include non-battery technologies (e.g., fuel cells). For clarity with AHJs, consider “Standalone BESS (Energy Storage System)” on first use, then stick to BESS or ESS consistently across drawings, studies, and submittals.

What Successful Standalone BESS Projects Have in Common

1. They model early. Reactive power, voltage regulation, charge/discharge windows, and ramp rates are baked into load flow studies before the pro forma is final.

2. They design with operations and auxiliary functions in mind. Access and SCADA architecture are part of the 30% design, not late add-ons.

3. They co-develop with utilities and AHJs. As Mudit put it, after initial meetings, “the whole department is now educated, and they’re giving really good, insightful comments.”

4. They right-size interconnection. Teams balance desired MW export with KVA overbuild and realistic grid upgrade budgets so the economics hold.

As Lakhan summed it up, the real challenge isn’t the battery technology itself, it’s what happens after you’ve stored the energy. How do you move it, control it, and monetize it within the constraints of the grid? The best Standalone BESS designs answer that question holistically: electrically, operationally, and financially.

For more information on Standalone BESS or our solar + storage engineering services, please fill out our contact us form or email info@PurePower.com.