Pure Power has provided clients with professional services for more than a decade, including electrical, structural, and mechanical engineering, energy modeling, project development support, and PV plant performance analysis and reporting. The underlying goal of all these services is protecting and optimizing the project owner’s interests. As C&I and utility projects have continued to scale and new disruptive technologies have entered the market, our team has gained hard-fought experience in the field as early adopters.

Disruptive solar and energy storage technologies can create impacts that ripple through all project phases from design and procurement to installation and commissioning to O&M. Exploring the shift from “big iron” central inverters to 3-phase string inverters in some large-scale systems is an opportunity to illustrate how Pure Power’s experience enables us to de-risk systems. Here is a look at how new products and even new manufacturers can impact your projects’ success and advice on how to hedge your bets on early adoption.

Product Evolution and Issues

Around 2014, the market began to shift to transformerless 3-phase string inverters for C&I and small utility systems. These inverters promised to meet new code requirements such as arc fault detection and rapid shutdown. The decentralized PV plant design options that string inverters provided offered more resilient systems and seemingly simplified O&M. Today, large-scale projects using string rather than central inverters are common, predictable, and high-performing. They also have a well-understood operational history. But the path to this point of predictability had significant obstacles.

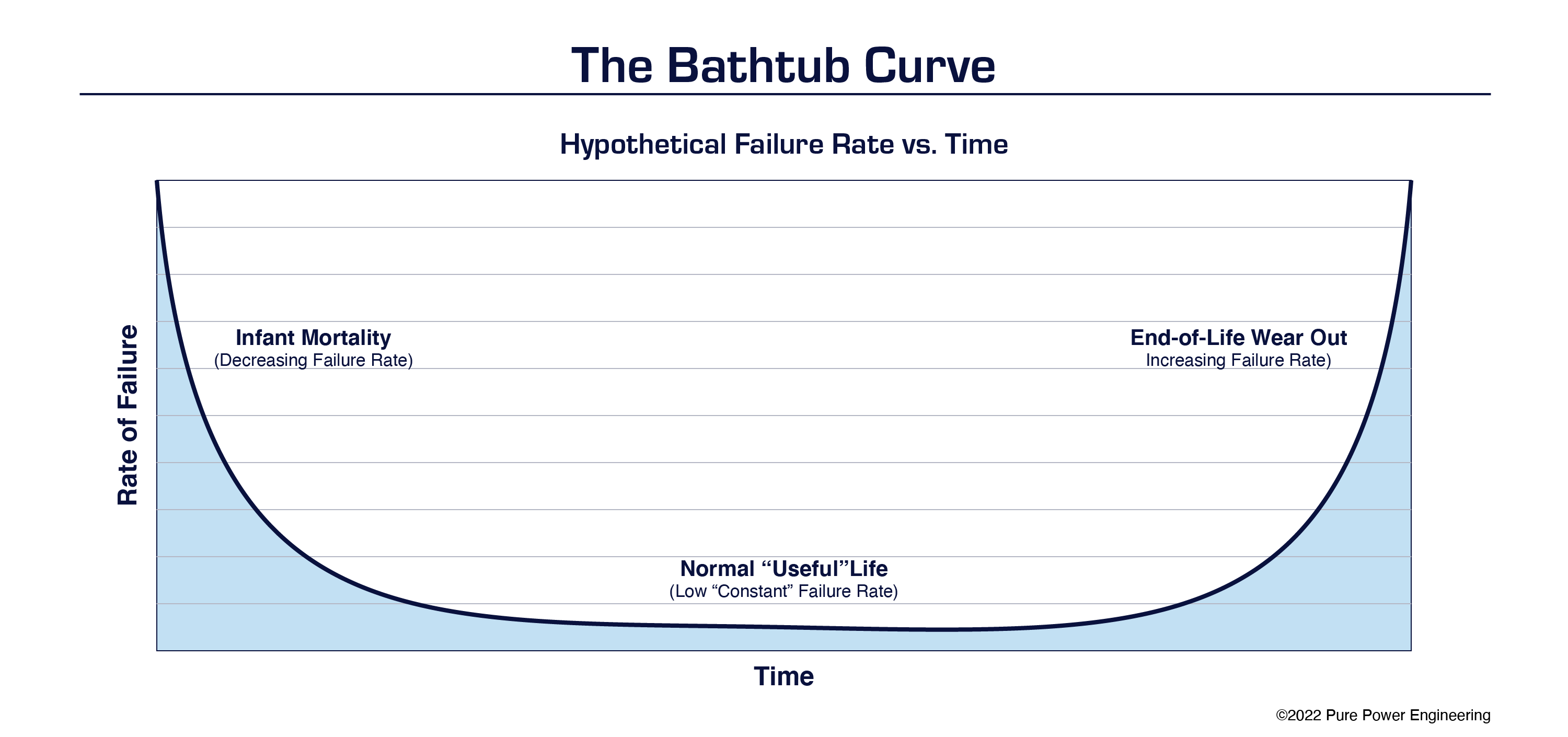

What generation is the product? An important insight that only experience can bring is recognizing the incremental improvements each new generation offers of a given product. The failure of recently launched, unstable new products does not always occur right out of the box or even in year one. The impact of these first-generation products can be stretched out for a few years. There is a long tail with some of these widespread failures. For example, first-generation 3-phase string inverters typically operated at 1,000 Vdc with a capacity range of 20 kWac–30 kWac. Over time, hardware and software upgrades resulted in a stable and reliable product and a platform to build on. The next generation of 50 kWac–60 kWac string inverters, which shared topology, hardware, and form factor, had an acceptable failure rate and in-the-field performance right out of the gate. In turn, some third-generation string inverter models made the jump to 1,500 Vdc, which is significantly different in terms of product design and component changes. If the product is not a direct descendant of an existing and proven platform, there is no guarantee of reliability at launch. As a proven example, even Toyota can have issues with early products that continually improve with each new model year.

Courtesy NREL

Codes and standards drive product development. Early adopters often face a lack of clarity in codes and standards as they apply to new, disruptive technologies. On the flip side, new codes and standards may push product go-to-market timelines to the point where manufacturers release products that are not ready for prime time. Market and business pressures can lead to condensed beta testing timelines, resulting in unstable products entering the marketplace. An example that solar professionals felt industry-wide was the unacceptably high occurrence of nuisance tripping in early 3-phase string inverter arc fault detection systems. The result? Costly truck roll after costly truck roll and eroding project profitability. It took manufacturers approximately a year and a half of software and firmware upgrades, new digital filtering, and hardware changes to reduce nuisance tripping to an acceptable level.

Set yourself up for success, not failure. Based on the historical track record, new or fundamental product design changes result in an uptick of failures, cycles of refinement, and become stable over time. However, the elephant in the room with new product introductions is that companies often don’t plan for higher-than-expected failure rates. If you plan on a typical 1 in 10,000 failure rate per year, which is typical for mature equipment, plan on failure rates of 1 in 100 or lower until the product has reached its stability plateau. Budgets and workforce capacity should account for this. Additionally, account for inverter replacement inventory, downtime, lost revenue in financial models, and perhaps most importantly, customer dissatisfaction and managing expectations.

Manufacturer and Form, Fit, Function Considerations

It is natural for manufacturers to strive to develop innovative and disruptive equipment. Differentiation can solve specific problems and help manufacturers capture market share. However, differentiation is not always a good thing for the customer. Standardization and commoditization allow for form, fit, and function replacement. Additionally, as noted earlier, issues tend to reemerge with each major new product launch.

In through the out door. Occasionally we are not just considering a new product, but a new product and a new company. In many cases, the latter presents solar professionals and project owners with the most significant exposure. Historically, the popularity of string inverters in C&I and small utility projects led to a rapid expansion of string inverter models and new market entrants. The contraction that followed was not surprising considering the overly crowded product space. Manufacturers with poor track records either faded into the background of the U.S. market or exited entirely.

The importance of form, fit, and function. At Pure Power, one of the things we look for when specifying string inverters for C&I and utility projects is a commoditized design in terms of form, fit, and function. Today, I am confident that if I have a significant problem with a brand that offers a standard 60 kWac, 1,000-volt 3-phase inverter, I will be able to source product from another manufacturer that provides an easy replacement, at least in terms of form and function. However, things get trickier when considering products with unique topologies such as proprietary module-level power electronics (MLPE), where there may not be a suitable replacement product if necessary.

Set yourself up for success, not failure. Pay attention to manufacturers with a limited or fading catalog. Typically, there is a two-year development cycle to launch a new product and a year to modify or improve an existing platform. A broad product catalog provides insight into a company’s commitment to the market. Companies without a recent launch or any fundamental product changes over a few years may be signaling a market exit. If you are experimenting with a novel topology or even with commoditized products, procure enough spares to manage project life. If the manufacturer shows signs of exiting the market, procure additional units.

Courtesy Sungrow

In-Use Considerations

Today, many 3-phase string inverter models suitable for C&I and utility projects have enough operational history to consider them as very stable products. However, confidence in a product’s reliability is only one aspect to consider. For example, shifting from a central inverter to a distributed string inverter system architecture has far-reaching operational impacts on activities, including O&M.

Repair it or swap it? For obvious reasons, central inverters are designed to be field serviceable. An attractive aspect of distributed string inverter systems trades field serviceability with field replacement. On the surface, simply swapping out a string inverter sounds painless. But be aware that you may be replacing more of them, especially when installing early-generation models. Additionally, you will need to add a process for procuring, stocking, and deploying spares, which was not a consideration with central inverter systems.

Compare warranty details. Another area of impact is warranties. With centralized inverter systems, the industry enjoyed parts and labor warranties because they are field serviced rather than simply replaced. A shift to string inverter systems ushered in parts-only warranties, often with no compensation for truck rolls. The high failure rates of some first-generation string inverters ate into project profitability where parts-only warranties were in place. To their credit, over time, several string inverter manufacturers introduced programs that better-supported integrators through service labor cost reimbursement programs.

Update commissioning and testing methods. Finally, disruptive new technologies usually require updating commissioning, performance, and O&M procedures and reporting. For example, legacy procedures and test methods will no longer be applicable with a shift from standard to proprietary MLPE-based string inverter platforms.

Set yourself up for success, not failure. Ensure that agreements take technology into account when considering test plans, so there are no bottlenecks such as IV curve tracing optimizers that cannot be turned on without energizing the array. Events like this can hold up milestone progress unnecessarily. Also, ensure O&M plans consider the unique variables presented by each equipment’s warranty terms.

Stakeholder Perception

Project stakeholders, including lenders, tend to shy away from systems with products that do not have established reliability and performance track records based on fielded systems. It is not enough to have a third-party report that deems the product or project to be bankable. There is a period of operation that has to happen before there is confidence in that information. Even manufacturers with excellent track records may have problems with a new product. Keep in mind that manufacturers that have responded well to past product issues are more likely to be good, ongoing partners moving forward. Ensure that your finance partners are comfortable with any new product considerations to avoid late surprises in the project design and planning.